Re:filtered #10: Democracy crumbles in darkness

Welcome to the 10th edition of my monthly newsletter on civic media opportunities in a moment of systemic disruption.

This month: journalism as a service, and celebrating a small research breakthrough.

A few weeks ago, I committed what felt like journalism heresy:

At a workshop I hosted in Portugal on supporting dissident media through technology, I suggested that maybe we're being a little bit too sanctimonious about this whole journalism thing. I suggested that we need to have more demand-side conversations.

Many of the technologists and media activists from Azerbaijan to Russia to Iran to the U.S. had joined the conversation probably expecting the usual hand-wringing about misinformation, disinformation, and platform politics.

The reactions at first: Uncomfortable shuffles. Confused looks. The kind of silence that follows someone pointing out that the emperor's new clothes might not be all that spectacular.

Some eventually left slightly befuddled for another panel, while others got it. We discussed how to build for relevance, both in terms of technology and editorial strategy. How do we address the growing disconnect between dissident media and societies? It was great.

I have come to see this step as a precondition to any meaningful conversation about media strategy. That's why at the beginning of my research workshops this year I have begun to challenge participants to question journalism's presumed importance.

Not because great journalism isn't worth the risks of producing and distributing it – it absolutely is – but because treating the performance of journalism wholesale as some mystical force that's inherently good regardless of its actual utility to people can be fatal.

It risks holding anyone nobly pursuing this profession back from actually being effective. And it gives a veneer of legitimacy to those abusing the craft and its increasingly scarce resources.

To illustrate our field's excessive sanctimony, consider this parallel: What if we treated local bakeries the way we talk about donor-funded public interest newsrooms?

Just like bread that's baked but not eaten serves no purpose – no matter how nutritious – isn't journalism that's produced but not consumed equally wasteful?

Like any successful bakery, civic media organizations have a responsibility to their communities to understand their attention market, meet real informational or emotional demands, and deliver value – before considering secondary aspects like packaging or distribution methods.

My resulting initial draft depicted a parallel universe in which baking had taken on all the trappings of non-profit journalism. It had puns on gluten fatigue, Monthly Active Eaters (MAE) dashboards, and impact playbooks by the National Endoughment for Democracy. It was so silly, I ultimately decided against sharing here.

The point, however, still stands. The tragedy is that in a moment in which journalism could be incredibly important we may be missing the how and why of consumption, assuming inherent value of whatever we're doing.

Over the past few years, voters in a growing number of democracies have been voluntarily handing power to populist authoritarians – figures whose true aim is self-enrichment, cynically hidden behind performative tribalism.

While we may not have been able to stop this, perhaps we can now prepare for what comes next. Journalism as a craft is perfectly equipped to unmask these kleptocratic motivations. But to be effective, newsrooms must think about earning attention from people.

It gives me hope that more journalism practitioners are asking these questions and are open to such conversations.

Read this from Frank Shyong, a former LA Times columnist:

Journalism institutions don’t see the deterioration of this social contract because we do not tell an objective story about ourselves. That failure leaves a lot of journalists confused about who we are, what our institutions represent, and why we’re doing this work. We believe ourselves to be heroes and are confused and angry when we are greeted as colonizers and corporations. We lecture the public and demand that they acknowledge our value with subscriptions and do not ask why no one is listening.

...

I don’t believe journalism is dying, even if its institutions always seem to be. Journalism is practiced by all kinds of people everywhere, regardless if there is a professional organization or journalist involved. Anyone who shares information in the public interest, who accepts responsibility for the public’s need for information and tries to get it correct, they are a journalist in my book. Journalism’s principles and practices are created by the public’s desire to know the truth, and that will never die. Good journalism, professional journalism, depends on how serious, how sacred your contract with readers is.

Shyong writes that he believes that "journalism won’t survive if it’s left in the hands of journalism institutions" and that's why he moves to Substack, "hoping to write my own contract with the public."

I actually believe in newsroom institutions. I believe that they can be amazing support networks for talent and extremely effective, if done right.

But that also requires them to be stepping off our sanctimonious pedestals and confronting harder questions about service before assuming that output has inherent value, and before thinking about distribution.

No theory of change works if the produced journalistic content, no matter how literary or sophisticated or revelatory, doesn't resonate with real people.

That's the fundamental flaw in how audience research is often practiced in newsrooms that I've been thinking about for months, and that I have been working on changing in my small ways.

Newsroom expectations on audience research have been, at least in my experience, way too often centered on finding distribution opportunities for content, rather than finding needs that could be identified, defined, and then intentionally met – and I don't mean the shallow need formulations like "update me" etc. that don't address underlying flaws in strategy.

All this forced squaring the circle of research leads to very convoluted and abstract constructs that mistake tactics for strategy.

Let's perhaps institute a test: if something sounds silly for another industry, then let's drop it. Let's stop being so precious.

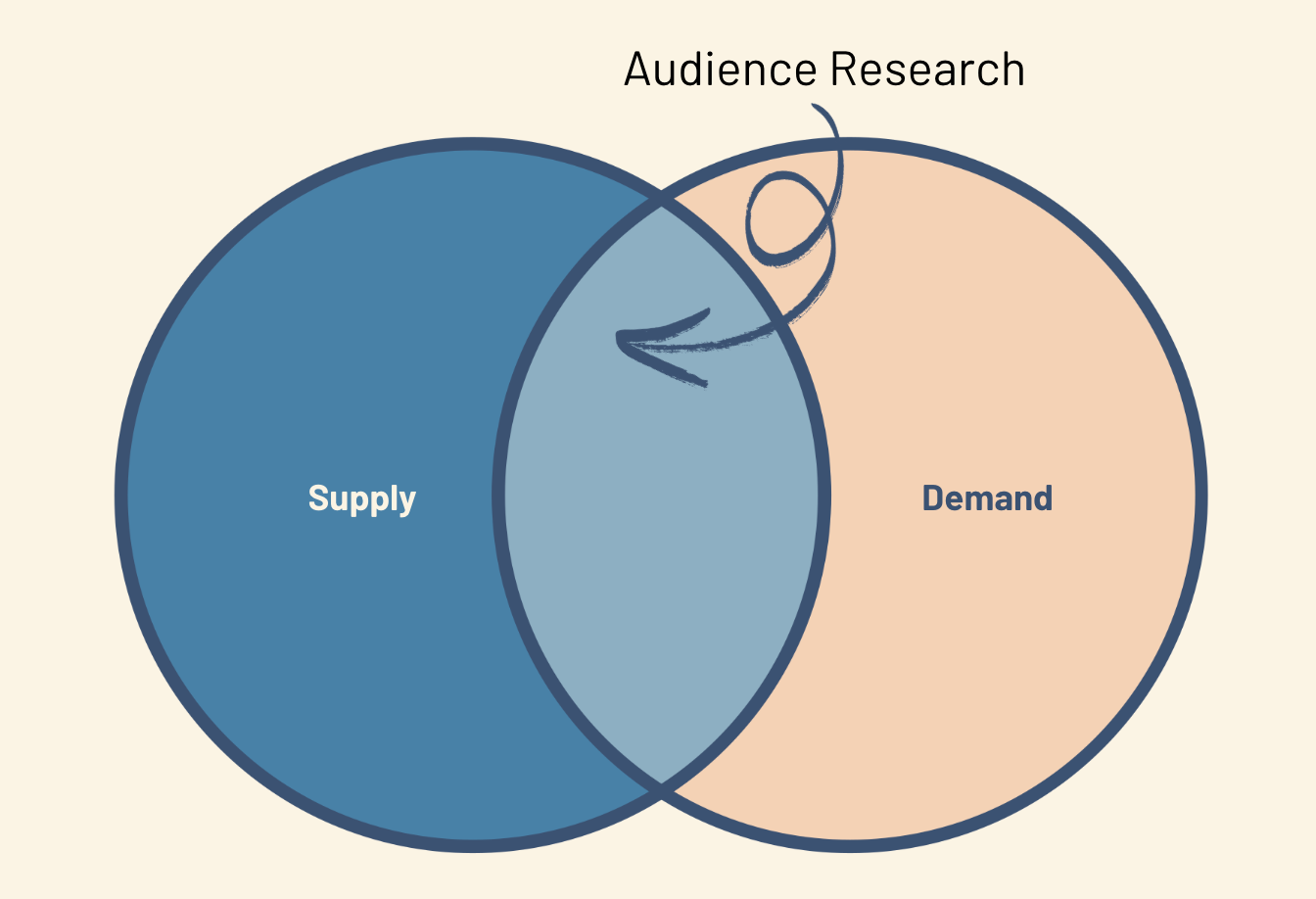

I've mentioned in earlier newsletters how I think of media organizations much like restaurants. Much like at eateries and bakeries, there needs to be some overlap in demand and supply. That has gone haywire with platforms distributing "content" to millions of people without a need for choice to happen.

(A real-life equivalent to getting traffic from search and social that comes to mind are the well-connected restaurants that Chinese tour groups are shepherded to anywhere in the world. As a former participant of such tours, I can tell you, none of these restaurants are ever any good, at least for the eaters.)

As social media fragments and news organizations can increasingly less rely on them and Google search for gratuitous or cheap distribution to what are essentially borrowed audiences, we journalists are now forced to slowly emancipate ourselves from our one-sided reliance on the big content platforms.

It's as good a moment as ever to rethink audience research not just on a tactical level like shifting to first-party data and optimizing for discovery or retention or finding "needs angles" to stories, but to reflect strategically on the core services we want to provide.

Here's a slide I use at workshops to make a case for structured thinking about identifying opportunity spaces for publishing through audience research:

Over the past few weeks, I've been buried in audience research work that aims to be useful for this next moment in media not in a big picture blah kind of way or on the narrow level of tactical optimization, but really concretely in identifying real journalism opportunities through demand-side research.

Building on the work of many, especially the work done in the U.S. on Civic Information Needs, my team and I have gradually found ourselves approaching demand systemically in a process that feels like a promising start. We did some creative work – that for months very well-resourced people in this space had been telling us was impossible – and I'm mighty proud we pulled it off.

(I do apologize for sometimes being overly circuitous in my descriptions of where and what we do as I navigate communicating the work without risking its disruption, or worse.)

We found that the methodology for understanding information needs is largely consistent across free and autocratic societies.

Like market research for a new bakery, we need to understand local conditions, demands, and constraints everywhere. What varies between Brooklyn and Pyongyang isn't the questions we ask, but how we gather answers and our confidence in specific findings that then form an overall picture.

Each element of information comes with its own confidence level, shaped by the tools and access available in each context. Yet when these elements come together – even in the most challenging environments – they form a surprisingly coherent picture of information needs.

We have developed two prototype methodologies to help move beyond content-first thinking:

- Newsroom workshop: A hands-on exercise where journalism teams get together to create a news product value hypothesis:

- Map what they know about their communities

- Find gaps in local information needs

- Look at how information currently moves

- Place informed bets on useful ways to fill these gaps

- Test and improve with community input

- Extensive research process: A far more detailed research effort that leads to a clear and sized understanding of defined news product opportunities:

- Maps information patterns by identifying key mindsets, from active seekers to careful doubters

- Matches needs to mindsets, understanding what each group wants and trusts

- Spots barriers unique to each mindset group

- Validates findings across different behavioral patterns

- Sizes opportunities based on how many people fit each mindset

We've tested these approaches so far once each in two different contexts, and discovered concrete opportunities we would have missed with traditional content-first thinking or ecosystem analysis.

What sets this apart is that we start with empathy on concerns, worries and aspiration, not content ideas or platforms. We focus on concrete information utility rather than theoretical value.

If you're interested in either exploring these approaches or helping develop them further perhaps in the new year, let me know.

Looking back

Voila the slides Becky Pallack and I presented on lean audience research at the News Product Alliance Summit earlier this month in a session called "empathy without exhaustion."

Becky is a co-founder of the excellent local news non-profit Arizona Luminaria. In our conversations, we found that we had very similar research challenges despite our different contexts. Becky had some really fantastic insights on how to get a newsroom excited about research.

Looking ahead

My former co-lecturer David Bandurski is kindly organizing a China Media Project brunch conversation with me titled "Carving Space for Journalism's Future" in Taipei Nov. 2. Message him or me if you're in town and interested in joining.

I'll also be at the Taiwan and Southeast Asia Civic Space Forum (if typhoon Kong-rey allows), and working on some ideas for RightsCon next year.

Using this opportunity to plug David's work: A few years back, he wrote a fantastic book about villagers on the outskirts of Guangzhou who refused to give up the land their families have cultivated for generations to well-connected real estate developers.

Their story speaks to the fundamental contradictions of economic development in mainland China over the last years, and the abundance of information space opportunities.

Nov. 4-8 are special because I get to return to Chiang Mai, where I haven't been in a decade, for Splice Beta to talk about what dissident and exiled media have taught me about media strategy.

In both Taipei and Chiang Mai, I am interested in meeting folks working on internet freedom and media research/strategy.

We are working on a few projects including furthering the audience research processes above that may be of interest for entrepreneurial renegades of all kinds, especially full stack developers.

I am grateful for introductions and always enjoy (re)connecting over coffee. You can reach me by replying to this email or on Signal.

Later in the month, you'll also find me in New York, DC and Warsaw, Poland. As always, I'll share the slide decks of public presentations with subscribers of this newsletter.

I'm also starting to plan my commitments for 2025. If you have any ideas for panels or workshops, let me know. I definitely want the team to do more work with more newsrooms and deepen our research expertise.

It's so fulfilling to do something that may actually be useful, without the tiring sanctimony I have had to adopt in some past jobs. There's a lesson for funders: stop expecting people you support to provide you with hyperbolic blah. Make sure they can be of service.

That's it from me this month. Thank you for reading. Your feedback – whether via coffee or email – makes this work more meaningful.

If this newsletter has been forwarded to you, consider subscribing (for free). You'll get a monthly dose of reflection on opportunities for civic media.

This article was not made possible by a grant from the Meta Democracy Cookies Initiative and the International Fund for Public Interest Baking.

Impact Metrics: This story generated three multilingual panel discussions about flour resilience, one highly engaged tweet about bagel strategies, and zero actual pastries.

Additional Support: No actual baking was performed, but several bakeries across four continents strengthened their strategic planning capabilities through innovative grant application deployment.